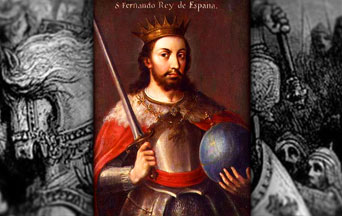

Saint Ferdinand – Born 1198, died as Confessor on 30th of Mary, 1252

In the traditional images of the liturgical seasons used by Dom Prosper Gueranger, the season of Christmas has the Emperor Charlemagne depicted as guarding over the manger of our Lord, with his imperial crown and “a sword in his fearless hand”. In the season following Easter Day, by our Lord’s sepulchre, there is depicted “Ferdinand the Victorious”, also wearing a crown and “keeping guard with his valiant sword, the terror of the Saracen”.

The Catholic tradition is sometimes understood as being full of religious people who have consecrated their virginity to God and devoted themselves to study, prayer, and almsdeeds, and indeed, the majority of saints who fill the calendar fit this role, in the same way that our Lord Jesus Christ spent thirty years of His Incarnation in humble subjection, silence, and modest labor, advancing “in wisdom, and age, and grace with God and men”, three years in public ministry, and only forty days in victory on Earth before His Ascension. Hence why there is given to us the examples of men of leadership, of kingdom, of glory, and also of the married and familial life, in a smaller amount.

One of the most shining pearls of these saints is Ferdinand III, King of Castile and Leon. He was the son of the holy and wise Queen Berengera, who was the sister of the holy and wise Queen Blanche, mother of St. Louis IX of France. Berengera had been obliged by the pope to leave her husband, Alphonsus King of Leon, and return to her father Alphonsus King of Castile because of a flaw in their marriage which had not received a dispensation, after having born two sons and two daughters, the eldest of which was our saint. He was made a lawful heir under Church authority.

Berengera’s father was an excellent king and died when Ferdinand was only fifteen years old, followed shortly by his queen. His son Henry was under age and required a regency, which is when an adult guardian is appointed to see to the affairs of a kingdom while the king comes of age. This was given to Berengera in recognition of her wisdom and virtue. She, however, preferred retirement in the religious sense, and gave the regency to a wicked man named Don Alvarez, who involved the kingdom in many unnecessary troubles. At fourteen, King Henry died of an accident, and Berengara claimed the throne for her son, Ferdinand. Still young, our saint ruled the kingdom “by his clemency, prudence, and valour” while it was involved in years of civil wars and trouble caused by Don Alvarez and others, and this principally because of his good mother’s counsel and advice. “No child ever obeyed a mother with a more ready and perfect submission than he did Berangera to the time of her death”.

Long before the birth of our saint, at the time of our Lord’s Ascension, Caesar’s son reigned over Rome, awaiting its conversion by St. Peter, and the region of modern Spain, called Iberia, was a firm province of that empire, having been won from Carthage in the time of the Roman Republic. St. James the Great, one of the three foremost in the College of Cardinals, traveled to Spain to convert it, and established the beginning of Catholicism there. It endured civil war but still remained Roman all the time through Constantine, converting to Catholicism completely, and being far from the empire’s enemies, until the time of the Goths. Barbarian tribes had taken the further part of Spain and Portugal, and Rome employed the Goths to combat them, who became the Visigoths, or western Goths. These are the progenitors of Catholic Spaniards today. They converted under Gregory the Great, St. Leander, and St. Isidore of Seville, having before fallen into Arianism.

In the East, after the death of St. Simeon, successor of St. James the Less in the bishopric of Jerusalem, being the last of the Apostles, heresies broke out constantly in the areas near to the Holy Land. According to Reverend Alban Butler these prideful heretics were before constrained by the eminence of those who had seen and followed Jesus before His Crucifixion. After that holy generation went to its rewards, because of these sins, God suffered the Holy Land to be chastised by pagans, especially the Persians, who worshipped the stars. This warfare continued and found its greatest persecutor in those who followed the moon, that is, the crescent, under Mohammed the false prophet and founder of Islam, which originally was understood as a schism and heresy from the Catholic Church. Through war, Islam conquered the Holy Land and all of the adjacent lands up to the borders of the Eastern Empire in modern Turkey, which had not yet entered into permanent schism. That would occur in the year 1054 under the pretense of the doctrine of the Filioque, that the Holy Ghost proceeds from the Son as well as the Father, which the Greeks denied. In consequence of this error (considered by many as a specious reason to explain the true distaste which the Eastern Churches had from the primacy of the Roman bishop), God allowed the capital of the East to be taken by Muslims on the feast of Pentecost, when the Holy Ghost came down on the Apostles.

Islam conquered across Africa and reached lower Iberia, or Hispania, in the year 711. In consequence of the licentiousness of the Visigothic king and the unjust wars which were conducted between Catholic kingdoms with the enemy at their very gates, God allowed Islam to conquer all of Hispania in a very short period, pushing the native Visigothic Catholics into the mountains, martyring many holy saints inspired by St. Eulogius of Cordova, and pushing into modern France until Charlemagne’s grandfather halted them, Charles Martel or Charles the Hammer.

The Reconquista is the long period between the Muslim conquest of Spain and their final expulsion in 1492 which began with Our Lady of Covadonga. This was a statue of our Lady in a cave in Asturias where it had been hidden by a hermit and which was found by King Pelayo, a Visigothic Catholic king who never submitted to the Muslims, and who found the cave and prayed to the Virgin for victory against the Muslims when they set out in much greater numbers to destroy this last resistance. Many miracles attended the victory, preceded by an apparition of the Mother of God bearing a shield with the name of Jesus and encouraging King Pelayo and his men. King Pelayo ruled a kingdom at that time that extended only ten miles in every direction, and he had only three hundred men. It is a sign of the destitution of our times that we are more familiar with three hundred pagans resisting a Persian invasion than we are these saintly Catholic warriors and sons of Mary.

The Reconquista lasted eight hundred years. Saint Ferdinand was born in the middle of it, when Islam controlled roughly half of Iberia and was a dangerous and dominant force. After becoming King of Castile, he would go on to accomplish the majority of the process of Reconquest from the infidels.

He did all this by incredible meekness, simplicity, and purity at a time where God continually punished Catholic kings for letting themselves be embroiled in war with their fellow sons of Christ by their pride. Not only did he obey his mother in everything, but he refused to ever go to war with another Catholic, no matter how much claim he might have. He had no interest in the things of this world. His own father, the king of Leon, declared war on him, and he meekly suffered this injustice. Then, when his father died, he inherited that kingdom. The pope, too, wrote him a letter saying, “I see that you have the charism of battle”, and desiring him to go on Crusade for the Holy Land against the enemies of God, a worthy temptation, to which this saintly and simple king responded, that there were plenty enough Muslims in his own lands with which to war. For it is not right to pursue great acts of magnanimity before observing all of the duties of our own station, no matter how humble, and for a king that means providing for his own people first, as a father provides for his own household.

Perhaps in observing his virtues in which he modeled himself after our Savior, being meek and humble of heart, we should obscure his great glory and victory in battle. Dom Gueranger says, “His life was one of exploits, and each was a victory. Cordova, the city of the Caliphs, was conquered by this warrior Saint. At once, its Alhambra ceased to be a palace of Mahometan effeminacy and crime. Its splendid Mosque was consecrated to the Divine Service, and afterwards became the Cathedral of the City. The followers of Mahomet had robbed the Church of Saint James at Compostella of its bells, and had them brought in triumph to Cordova; Ferdinand ordered them to be carried thither again, on the backs of the Moors.

“After a siege of sixteen months, Seville also fell into Ferdinand’s hands. Its fortifications consisted of a double wall, with a hundred and sixty-six towers. The Christian army was weak in numbers; the Saracens fought with incredible courage, and had the advantages of position and tact on their part: — but the Crescent was to be eclipsed by the Cross. Ferdinand gave the Saracens a month to evacuate the city and territory. Three hundred thousand withdrew to Xeres, and a hundred thousand passed over into Africa. The brave Moorish General, when taking his last look at the City, wept, and said to his Officers: ‘None but a Saint could, with such a small force, have made himself master of so strong and well-manned a place.’”

Our saint also intended to conquer into Africa, but God took him away before this could happen, and reserved the last victories of the Reconquista for those noble sovereigns, Ferdinand and Isabella.

Again, it is important to remember that victory in any endeavor follows the will of God, which generally goes to those who obtain it through virtue, as it says in Scripture, that with the blessing of God, one man may put ten thousand to flight, and with the curse of God, ten thousand will be in disorder and flight without a single enemy. Our saint, the father of his people, said, “I am more afraid of the curse of one poor woman, than of all the Saracen armies together.”

He was a close relative to St. Louis the Crusader, and these two shared many similarities in their militant spirit, their simplicity, their compassion for their people, justice, and the poor, and their devotion to their own mothers and the holy Mother of God. But it is pointed out that while Ferdinand’s life was one of almost unceasing victory, Louis’s was plagued by misfortune, and in this is an important lesson: Ultimately, the triumph is given to the Saints in Heaven, not on Earth. As Gueranger puts it, “as though God would give to the world, in these two Saints, a model of courage in adversity, and an example of humility in prosperity. They form unitedly a complete picture of what human life is, regenerated as it has now been by our Jesus, in whom we adore both the humiliations of the Cross and the glories of the Resurrection. What happy times were those, when God chose Kings whereby to teach mankind such sublime lessons!”

In his final agony, when the Blessed Sacrament was brought to him, St. Ferdinand climbed out of his sick bed, prostrated himself on the floor, put a cord around his neck, and received Communion. More can be said of this holy saint.

Saint Ferdinand, pray for us!